House of Representatives Date: 4 November 2025

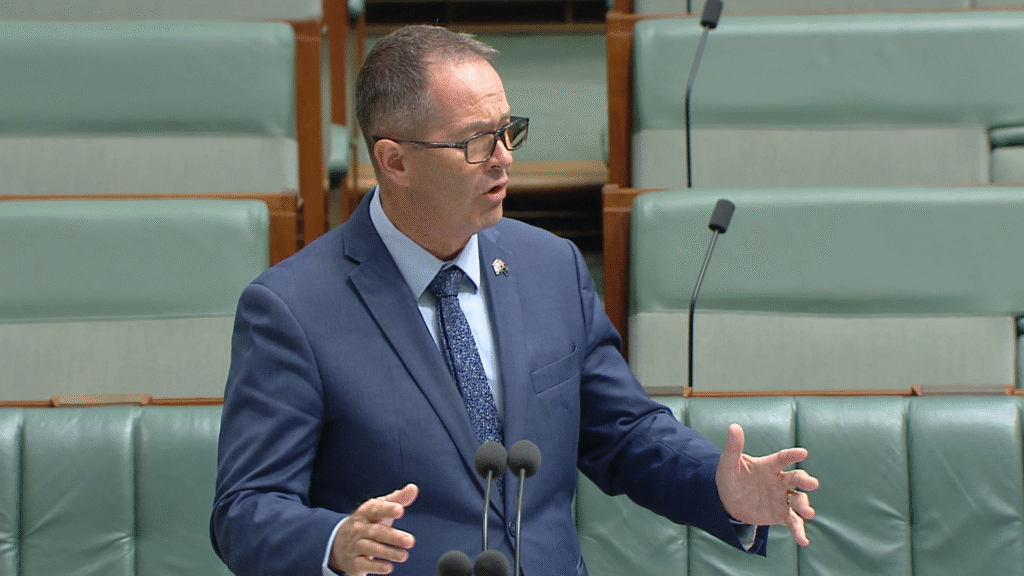

Andrew Wallace MP:

Freedom of information is not a privilege handed down by government. It is a right owed to the Australian people who elect us-that is, to serve them. When Australians ask their government for information, they are not being difficult. They are exercising their basic right of citizenship, and the documents of government belong to the people. This bill before us, the Freedom of Information Amendment Bill 2025, takes that ownership away. The government dresses it up as modernisation. I need to be very clear here. This bill does not modernise the Freedom of Information Act; it weakens it. In fact, it tramples it. It does not simplify access; it restricts it. Australians expect a modern Australia where transparency isn’t compromised or withheld, and they expect a government that speaks plainly, answers honestly and trusts the people with the truth. This bill moves the FOI system from a presumption of openness to a presumption of control. And that is a profound change to the character of our democracy.

Before I go further, I want to thank my colleagues the member for Berowra, the former shadow attorney-general and the Leader of the Opposition for their early and tireless work in exposing what this bill really means. They have articulated the stakes with precision and courage. The member for Berowra has called this bill for what it is: it’s a truth tax, a proposal that makes Australians pay to know what their government is doing. And the Leader of the Opposition has warned that secrecy is becoming the defining feature of this government.

The Leader of the Opposition is absolutely right. Since taking office, Labor has promised integrity but delivered opacity. The government has normalised non-disclosure agreements when consulting with stakeholders. They’ve written secret manuals instructing public servants how to answer Senate estimates questions. They’ve flouted Senate orders for the production of documents. And we already have a transparency problem under this government. In Australia, at the federal level, the proportion of freedom of information requests granted in full has fallen from around 59 per cent in 2011-12 to approximately 25 per cent in 2023-24.

Freedom of information operates as a practical tool for transparency and accountability. It is the mechanism through which Australians-journalists, charities, researchers and even ordinary citizens-uncover the truth about decisions that affect them. Effective FOI leads to greater openness in government. When it fails, mistakes multiply in the dark.

This bill has no allies outside government. Every credible transparency organisation, media outlet and integrity body has condemned it. When a law designed for openness can’t attract a single voice of support from those who champion transparency, that tells you everything you need to know. And the motion that was moved by the Leader of the House just before goes one step further, because this government doesn’t want this debate to be had in this main chamber.

On the Sunshine Coast, in my electorate of Fisher, people expect straight dealing from their government. They expect to see how that money is spent-how hospitals are run and how infrastructure decisions are made. Australia’s Constitution rests on informed choice. That means citizens must have access to information to inform judgements. Secrecy undermines that design. It unplugs the democratic machinery. In 2023-24 approximately 25 per cent of FOI requests were granted in full; however, 89 per cent of those were released with redactions, meaning just around five per cent of all FOI requests were released without any redactions. The problem is not too many FOI requests; it is too few answers. There are 967 unresolved reviews, and agencies are routinely breaching timeframes. That is not efficiency; it’s dysfunction.

Because the public will be the most affected by this bill, let’s look squarely at what it does. There are nine schedules to this bill. For the public benefit, this means the bill is divided into nine distinct part-nine steps backwards for transparency.

Schedule 1 rewrites the very purpose of the act. Where once the law said government information should be released unless there is a good reason to withhold it, under this bill it will say that information should be released only if doing so is consistent with the proper functioning of government. That is a lawyer’s trick. It’s a shift in balance so subtle that it hides its magnitude. Once you make the proper functioning of government an equal goal, you hand every agency an escape route-they can refuse disclosure, claiming it protects orderly government, and the culture of secrecy wins. Labor promised integrity and yet they deliver opacity. You can’t campaign on light and legislate for shade, but that is exactly what this government is doing.

Schedule 2 bans anonymous requests. The Labor government claims this will protect national security from bots and foreign actors. That argument does not survive contact with reality. Once a document is released under FOI it is public. Anyone, anywhere, can see it. Who the applicant is makes no difference to a hostile foreign actor, but it makes an enormous difference to the whistleblower, the advocate, the junior official or the citizen who fears reprisal. Anonymity protects the vulnerable; it does not endanger the nation.

Schedule 3 introduces a discretionary 40-hour processing cap. That is somehow sold as efficiency. In truth, it is permission to stop searching once things get difficult. The big, complex, multi-agency requests-the very ones that expose systemic problems-will be the first to hit the wall. It tells the public: your request is too hard, your question is too expensive and your patience is irrelevant.

Schedule 4 changes the statutory timeframe from 30 days to 30 working days. That may sound technical. It means six weeks instead of four. In practice, with extensions, delays and consultations, it means months before any decisions.

Then comes schedule 7, the most dangerous of them all. It expands the cabinet exemption to include documents that describe or refer to cabinet material. It therefore allows agencies to refuse requests without even searching for the documents. It broadens the deliberative processes exemption so far that almost any piece of advice or internal discussion could be sealed away indefinitely. That is not protecting cabinet confidentiality; that is institutionalising the prevention of political embarrassment. Factual material, which by long tradition should released, will now be buried alongside opinion. The release of unappetising political criticisms is a cross all political parties have had to bear-parties of government, at least-and it’s a crucial part of governing, because every government that has faced scrutiny has ultimately been strengthened by it. The result is that, under this bill, Australians will see only the announcement-never the debate or the consideration that led to it. Some may call this weakness; others will call it lack of accountability. It is both.

This bill is not an isolated act. It is a part of a pattern-a pattern of control, concealment and centralisation. We have seen the same instinct in the refusal to release modelling on energy policy, in the endless redactions on defence procurement and in the handling of the Prime Minister’s own diary. The Centre for Public Integrity has shown that fewer than one in four FOI requests are now fully granted, down from half just two years ago. That is the lowest level of transparency in 30 years-and that was before this bill. If this is how the government behaves under the existing law, imagine how it will behave when the law itself gives it a licence to hide.

Who loses when transparency dies? Not governments-they find it more comfortable. Not corporations-they have lawyers and lobbyists. It is the ordinary Australian who loses: the citizen who wants to know how their aged-care provider is regulated; the local journalist following the money trail through a community grant; the community legal centre fighting for a fair hearing for a client; and charities and not-for-profits across this country, already stretched, who cannot afford to pay new fees or wait another six months for an answer that arrives half-redacted, if they’re lucky. This bill would make the public’s right to know depend on the size of their bank accounts and the patience of their lawyers. That is not democracy.

The government says this bill is about efficiency. That claim deserves to be tested line by line. Efficiency is not achieved by making it easier to say no; efficiency is achieved by fixing resourcing, training and culture. It’s achieved by clearing backlogs, not legalising delay. Right now, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner is underfunded and overwhelmed. Applicants wait years for reviews. The commissioner’s decisions are often ignored. Instead of fixing that, this government proposes to narrow rights and expand excuses. It blames the public for using the law too well.

Let’s take a closer look at the new 40-hour processing cap. On the Sunshine Coast, if a citizen wants to see correspondence about a hospital project, an aged-care audit or a regional roads upgrade, they will likely need more than 40 hours of agency time to find and process the files. This cap says to those citizens: ‘Your question takes too long. It’s too complicated. It does not suit the government.’ What if the information exposes waste? What if it shows the department ignored warnings? The harder the search, the stronger the reason for disclosure-not refusal. If the government were serious about fairness, it would replace this cap with a duty to assist. Agencies would have to work with the applicant to narrow the scope and release documents in stages. That is what transparency looks like in practice.

Next, the bill introduces application fees, to be set later by regulation. A government that promised openness, transparency and accountability now wants Australians to pay to participate in their own democracy. As the member for Berowra said, this is a truth tax. You pay to play. You pay to see what your government is doing with your taxes. For big corporations, that may be fine. They can absorb that cost. However, for the small community paper in the Glass House Mountains, for the environmental volunteer group in Maleny, for the carer in Beerwah trying to understand why aged-care services were cut, those fees are an impermeable wall.

Freedom of information should not be a premium service for those who can afford it. It should be the ordinary right of every Australian. The ban on anonymous requests strikes at the most basic democratic protection: the ability to speak truth to power without fear. Imagine a public servant who discovers serious waste or wrongdoing. Under this bill, if they seek to test what documents exist or whether advice was followed, they have to do so in their own name. They must expose themselves to the very system that they are questioning. This bill tells public servants that concealment is safer than candour and that silence is the smarter career move. Anonymity has always been a safety valve for conscience. To remove it is to choke that valve closed forever.

The government hides behind talk of bots and foreign actors, but, as the Leader of the Opposition said in her article in the Canberra Times, Labor’s excuses about bots and foreign actors are a smokescreen. The real effect of these changes will be fewer documents, higher costs and more excuses to keep Australians in the dark. She is exactly right. This government talks about the importance of this bill impacting upon national security. They organised a briefing for the former shadow attorney-general and then cancelled it at the last minute and said, ‘If you want a briefing, it’ll have to be in the PHBR’-the Parliament House briefing room-‘but you’ll have to bring the home affairs shadow with you.’ That meeting has never happened, nor has it been offered to me as the new shadow attorney-general.

I’ll move on now to the expanded cabinet exemption. No-one disputes that cabinet confidentiality is essential to good government. Ministers must be able to deliberate privately, but this bill goes far beyond that. It protects not only cabinet papers but any document that merely refers to them. That could mean briefing notes, talking points or factual summaries prepared for other purposes. Under this test, almost anything could be claimed as cabinet related if it is politically awkward. As a former barrister, I can tell the House what happens next. The culture of refusal hardens. Every request touching a policy question is deemed cabinet in confidence. Every internal email becomes deliberative. Every appeal drags on until the issue is cold. That is not sound decision-making. It is the quiet consolidation of power carried out in the shadows where accountability cannot reach.

Perhaps the most audacious change is the power to refuse requests without even looking for the documents. Let’s pause there for a moment. The government wants agencies to say, ‘We have not checked, but we are confident it is exempt.’ That undermines every safeguard of fairness and review. If there is no search, there is no record of what was withheld, no basis for an appeal and no accountability for misuse. Even the small print matters. Changing 30 days to 30 working days adds more than two weeks to every request. Combine that with consultation extensions and remittals and a simple FOI can stretch into months. Time is not neutral. Delay kills stories. It exhausts citizens. It lets wrong decisions fade from memory before the truth emerges. The truth is that this bill is part of a much bigger picture-a steady erosion of transparency since Labor took office. Under this Prime Minister, fewer documents are being released than under any government in 30 years. The Centre for Public Integrity says compliance with Senate orders has fallen to record lows. This government has pioneered non-disclosure agreements in consultation with stakeholders. It has cut staff for those in parliament whose job it is to hold government to account. It has even tried to control what questions can be asked in Senate estimates.

Secrecy has become a reflex, not an exception. What happens when you legislate secrecy? When one hides their mistakes, they multiply. This breeds complacency. It hollows out trust. This bill does not make for good government. Freedom of information is not comfortable for governments, and nor should it be. It is supposed to make power uncomfortable. It is supposed to make us as politicians, as the executive, answerable. Governments that fear scrutiny do not trust the people, and, when governments do not trust the people, the people stop trusting government. That is how cynicism takes root. That is how democracies weaken. Trust is already an issue in Australian politics. The conduct of the now government when in opposition made it an election issue in the lead-up to the poll in 2022. The government’s hypocrisy on this issue is breathtaking.

Every day, I see the expectations Australians hold for their representatives, on the Sunshine Coast and right across this country. They expect their elected representatives to be honest, open and accountable. They do not expect every email or cabinet note to be made public, but they do expect the truth. In my own electorate of Fisher, people care deeply about how health funding is allocated, how infrastructure projects are decided, how modern families are supported and how aged-care providers are monitored. They have a right to see how decisions are made in their name, as do the 27 million Australians that live in this great country. At its core, the Freedom of Information Act is a statement of principle, that the information held by government is the property of the people. That principle has served Australia well for more than 40 years. It has allowed journalists to expose the misuse of funds. It has empowered communities to question decisions. It has led academics and advocates to improve policy. It is not perfect, but it is vital. This bill threatens to turn that principle upside down. It says information belongs to government unless the public can pry it loose. That is not the spirit of a free nation. That is the spirit of bureaucracy, not democracy. This debate is not only about law; it is about culture. It is about the kind of government we want to be and the kind of relationship we want with the people we serve.

I have the highest respect for our public servants. The overwhelming majority act with integrity, professionalism and pride, but the best way to protect that integrity is not to hide their work; it is to uphold it. Public servants deserve laws that reflect their commitment to the public good. They do not need laws that allow ministers to bury advice when it becomes politically inconvenient. When the Leader of the Opposition wrote that ‘transparency is not a burden on government but a duty of government’, she captured the essence of this debate. She reminded us that good government is not about avoiding discomfort but about being accountable for the decisions we make in the public’s name. That is the standard Australians expect from their representatives and their institutions.

Secrecy may feel safe for those in power, but it corrodes confidence from the ground up. It tells citizens that government belongs to a class apart, not to the nation as a whole. It says to the nurse in Birtinya, the teacher in Palmwoods and the small-business owner in Caloundra that decisions are made behind closed doors and that their right to question those decisions is conditional. That is how trust dies-not in one dramatic moment but in small acts of concealment, justified as efficiency or modernisation. A government that hides information is a government that forgets who it serves. The FOI system was built on a presumption of disclosure. This bill replaces that with a presumption of control. It rewrites the social contract between government and the governed. That is not reform; it is cowardice. Let me outline, instead, what genuine reform could look like.

First, restore the original object of the act. Transparency must remain the primary goal. Administrative efficiency can be achieved without making secrecy a competing purpose. Second, protect anonymity. Replace the ban with simple technology that filters bots and bulk spam requests while preserving the safety of individuals who act in the public interest. Third, abandon the 40-hour cap and replace it with a duty to assist. Require agencies to help applicants narrow scope. Release material in stages, if need be, and prioritise public interest requests. Fourth, narrow the cabinet expansion. Limit the exemption to genuine cabinet submissions, decisions and minutes. Exclude factual material and prohibit blanket claims over documents that only mention cabinet.

Fifth, delete the power to refuse without search. If a document is truly exempt, let that be shown through proper process. Refusal by assumption undermines both transparency and accountability. Sixth, cap or waive fees for public interest applicants. Journalists, charities, academics and community groups should not be priced out of participation in their own democracy. Finally, fund the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner properly. Delays are not caused by the public asking questions; they are caused by a system without the resources to answer them.

These are practical, fair and balanced reforms. They preserve genuine confidentiality where it is justified while strengthening the right of the public to know.

This debate also goes to the heart of public integrity. In Fisher and across the Sunshine Coast-in fact, across the country-people expect government to deal straight with them. They expect honesty in words and transparency in action. They see the headlines about redacted reports, missing documents and endless delays-and they just shake their heads. They ask, ‘Why can’t the government just tell us the truth?’ That question should shame any government that calls itself open and accountable. Transparency is not a partisan virtue; it belongs to every Australian who believes in fair play and honest government. Once secrecy becomes normal, its insidious nature is left to fester. It seeps into local councils, agencies and public corporations. It turns freedom of information into freedom from scrutiny.

History shows that governments rarely surrender secrecy once they have tasted it. That is why this parliament must stop this now, before the habit becomes the culture. If this bill passes unamended, the next government will face pressure to reverse it. The crossbench and the Greens have already expressed deep concern. That should ring strong alarm bells on its own. Transparency should be the common ground of democracy, not a battleground of ideology.

This is not about comfort for politicians; it’s about confidence for citizens. If the people can’t see, they can’t judge. If they can’t judge, they cannot trust. And when information is withheld, rumours rush to fill a void. Conspiracy replaces evidence. Distrust replaces participation.

Freedom of information is the antidote to that cynicism. It says: ‘Here are the facts. Decide for yourself.’ Every time an agency releases a document, every time a journalist exposes misuse, every time a citizen finds an answer through FOI, democracy is strengthened. That is why this bill matters so deeply. It is not technical housekeeping; it is a test of whether this parliament still believes that information belongs to the people. This bill fails every test, and I ask the House to oppose this bill as it is drafted. Do not vote for longer delays. Do not vote for higher fees. Do not vote for wider exemptions. Don’t vote for a truth tax on democracy.

Vote instead for transparency, honesty, and confidence in the people we serve. Vote for accountability, the true test of leadership. Freedom of information is not a nuisance; it’s a right. I call on all members of the House to reject this bill until it reflects the values of openness, accountability and respect for the people who sent us here.

Debate adjourned.

END

Media Contact: Brendan West – 0402 556 646 – Brendan.west@aph.gov.au